I’ve been reading a lot of articles about scientific journalism, and what Scientists and Journalists need to change in how they release new findings to combat public misunderstanding. There are some great ideas there, and a lot of people committed to making this happen. The problem, though, is that science has a lot of concepts and vocabulary that are either exclusive to science (and impossible for non-scientists to understand) or are used differently in a colloquial context. So I’m going to start small and pick one. RANDOM.

If you’re having a conversation with someone and the word “random” comes up, you’re likely to think “something completely unexpected,” or “something without precedent,” or “something that just makes no sense.” “Random” started off meaning one thing to scientists and mathematicians and another to everyone else, and now it’s becoming a catchword for many other things that are even further removed from the strictest definition of “random.” Pseudoscientists and peddlers of dubious ideas and products take advantage of this by using the new popular understanding of the word to misrepresent or even mock science that uses it, so I want to set you straight.

Let’s start off with a straightforward explanation. “Random,” in science or mathematics, refers to a set or subset of existing things that is separated, combined, or put in order without any plan or pattern.

Take a look at A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates. This book has been around for a long time, and it’s an important tool for checking probabilities and mathematical formulae to make sure that they work with numbers that have no patterns. It’s not a very exciting read, obviously, but what you will find if you look at it is pages and pages of numbers. In other words, you will not find symbols, color dots, letters, or little drawings of cats. The numbers are random because they cannot be placed in any kind of sequence – as a simple example, you wouldn’t be able to add three to the first digit, six to the next, nine to the next pair, etc.

If you were talking to your friend about this book of numbers that was, like, totally random, your friend might reasonably expect to find those symbols, color dots, letters, or little drawings of cats. But your friend would be wrong; that wouldn’t truly be random since none of those things exist in the set called “numbers.”

So let’s look at this from the point where I see most of the misinterpretation of “random”. . .genetics. I want you to imagine two bags of marbles. I’m not going to specify how many, because we’re not going to get started on the difference between chromosomes and genes or anything like that. We’re just going to be very general and say that each marble represents a piece of genetic information.

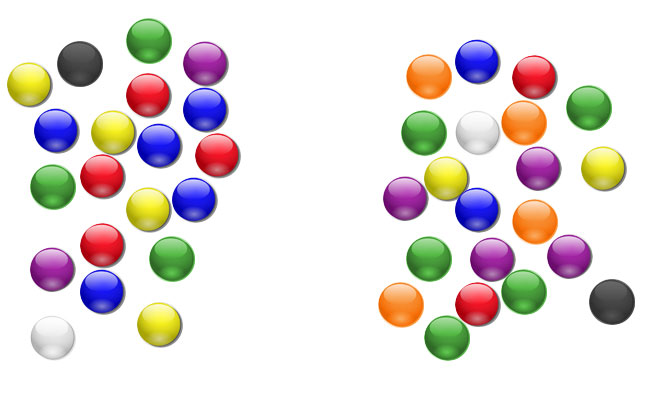

One sack is filled with marbles that represent Dad’s genetic information, the other is filled with marbles that represent Mom’s genetic information. Now let’s say that Dad’s marbles are almost all primary colors, but there are a couple of purples, a few greens, one black, and one white. Mom’s marbles are mostly secondary colors, but she does have a smattering of reds, blues, and yellows, and one black and one white. So you reach into the bags blindfolded and grab a handful of each, and this is what you come up with:

That’s random (although it’s unlikely that you’re going to get the single black marble and single white marble from each bag. I just wanted to use them.) Do you see any peach pits, or rocks, or silver marbles? Of course not. They weren’t part of the set from which you were randomly selecting. They’re not going to appear out of nowhere – and if they do, it’s not scientifically random.

Now let’s say that we’re going to pair them up. The only rule is going to be that the marble from Dad’s set can’t be paired up with the same color from Mom’s set. In real life, this happens fast, and the number of pairs is significantly bigger, but this is a decent symbolic representation. So across the top are the marbles we got from Dad, and below that are the marbles we got from Mom.

Randomly we ended up with a unique combination – but still, there is nothing there that wasn’t present in the original set. Randomly we ended up with an extra blue marble from Mom. It could have been an extra orange, purple, green, red, yellow, black, or white marble – but it could never be a peach pit, or a rock, or a silver marble.

You could take all these marbles and put them in different sequences, but nothing is going to change the number of marbles, the colors, or which marbles came from which bag. You might get different pairs of colors, or all the same pairs but in different order.

Randomness, in science or mathematics, means that we have certain things that are givens. A set of numbers will contain nothing but numbers. A set of genes will contain nothing that isn’t already in the genome. Any random thing we look at will be comprised of something very specific that already exists. What makes it random is how it ends up being put together.

I hope that makes sense. Feel free to ask questions or add to the discussion.