It’s been a while, and I’ve had a lot of stuff going on both in my life and in my mind, but I’m determined to finish this thing. Previous posts:

This is the section in which everything that was talked about before is kind of recapped and explained and, well, justified. I approached this in a much simpler format, because that’s really all it needs. My comments are bolded.

DISCUSSION

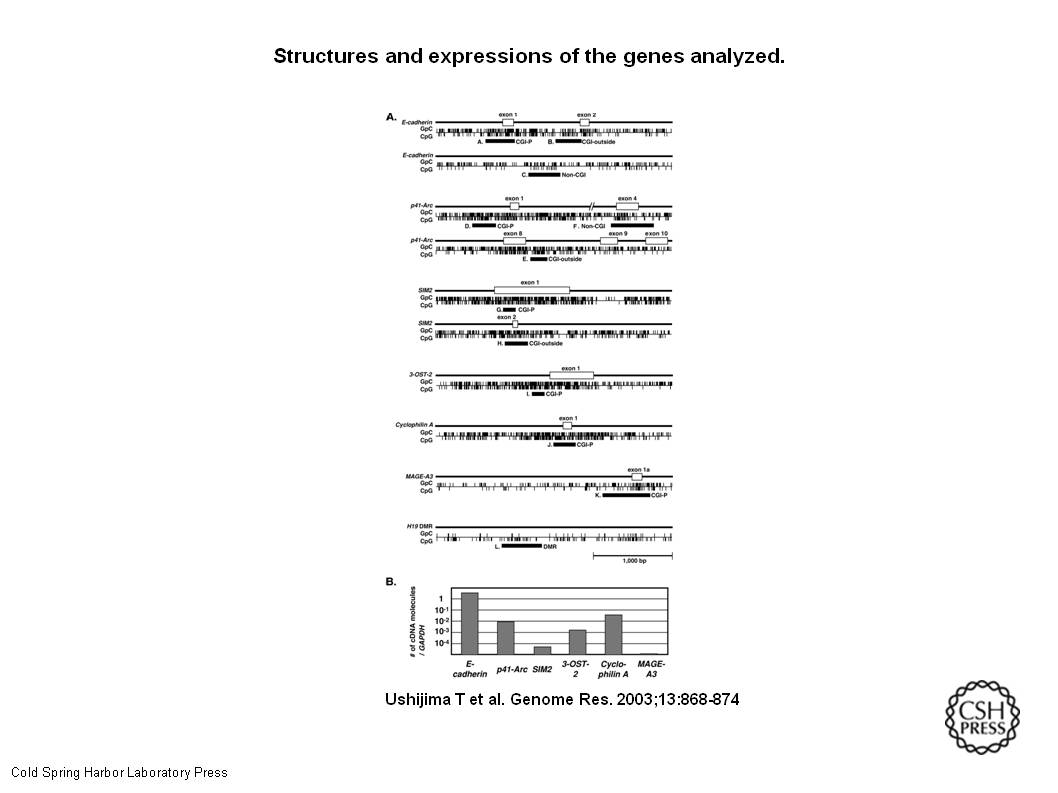

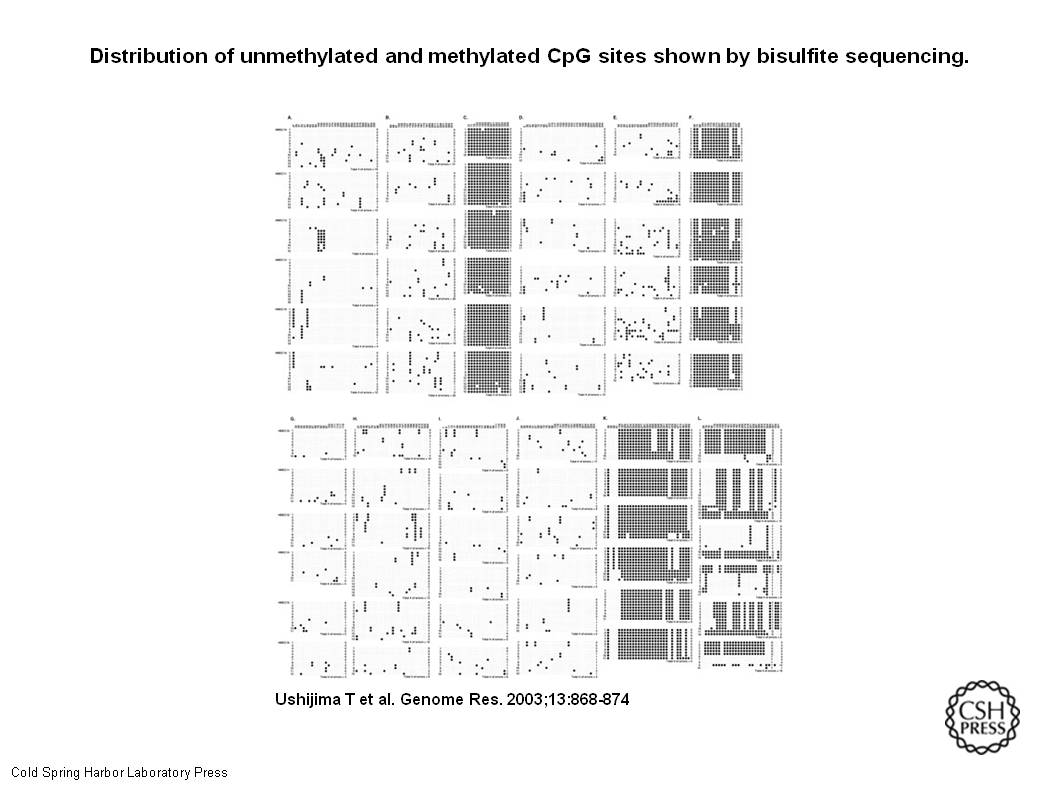

It was first demonstrated here that the fidelity of replicating methylation patterns of CGIs in the promoter regions is significantly higher than that of CGIs outside the promoter regions. (CGIs in promoter regions replicate themselves more accurately than the ones outside of promoter regions.) It was also demonstrated here that methylated genomic regions show much higher fidelity than unmethylated genomic regions. (If the genes are methylated, they tend to stay methylated, if they’re unmethylated, they can become methylated.) These showed that maintenance methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites into fully methylated CpG sites at DNA replication was highly reliable, while unmethylated CpG sites tended to be methylated by de novo methylation. (Methylation sticks.) It is well-known that exogenous DNA is exposed to a de novo methylation pressure (Doerfler et al. 2001; Bird 2002), and a similar methylation pressure seems to be working on the endogenous DNA. (Unmethylated sites are vulnerable to methylation from outside sources.) To maintain the unmethylated status of CGIs, protection mechanisms from the de novo methylation pressure seem to be necessary. (Unmethylated CGIs need something that protects them from methlyation or they’re vulnerable to it.) Since the MPERs were significantly lower in CGIs in the promoter regions than in CGIs outside the promoter regions, the presence of a protection mechanism(s) specific to the promoter regions, in addition to a mechanism(s) common to all CGIs, was indicated. (Promoter region CGIs probably have stronger protection against methylation of unmethylated regions, because they resist methylation better than non-promoter-region CGIs do.) Although the details of the mechanisms are still unknown, binding of transcriptional factors, such as Sp1, has been indicated as a promoter-specific mechanism (Han et al. 2001). (Hint, hint – this is something someone might want to look into, guys, ‘cuz our grant has been spent! Heh.)

The differential fidelities in replicating methylation patterns of CGIs in the promoter regions and those outside indicated that aberrant methylation of CGIs would occur at different rates depending upon their locations. This will be important when tumors are analyzed for the CGI methylator phenotype (CIMP), which are considered to be caused by molecular defects that allow accumulation of aberrant CGI methylations (Toyota et al. 1999). The differential fidelities shown here suggest that there are two types of CIMP, one due to a defect(s) in the protection mechanisms common to all CGIs and the other due to a defect(s) in the protection mechanisms specific to CGIs in the promoter regions. Actually, a correlation between the CIMP and the diffuse-type histology was clearly observed in gastric cancers when CGIs in the promoter regions were used for CIMP analysis (Kaneda et al. 2002b), while it was unclear when CGIs outside the promoter regions were used. (This will help us do more research that will help with cancer prediction/prevention/treatment, in case you don’t think that these findings have a worthwhile purpose of their own. When in doubt, reference cancer. For people with maybe a little less vision or curiosity. Just sayin’.)

In order for an impaired fidelity in maintaining a methylation pattern to exert any biological effect, methylation statuses of multiple CpG sites in a CGI must be altered. (One change at a single location isn’t going to make a big difference.) A significant increase of MPERs would be necessary for this, and quantitative analysis of MPERs in cells with suspected increase of MPERs is necessary. (We don’t know how many besides “more than one,” so another study would be required.) DMR of the H19 gene had a polymorphism at nt. 391 (nt. 8217; GenBank accession no.AF125183), and this served to distinguish the two alleles clearly. (This location was where we could best see what happened.) The G-allele was methylated in all of the six cultures, and the T-allele was unmethylated. The methylation patterns of the T-alleles were similar in HMEC11 and HMEC15, but were essentially variable among the six cultures. This indicated that, although the original cells in HMEC11 and HMEC15 might have had a common ancestral cell, methylation patterns in a tissue alter significantly during a human life span. (Methylation may change because of time, not necessarily because something came in and methylated stuff. No pointing at a specific environmental influence like a chemical or somesuch. Just demonstrating that it happened, and where and why it would be more or less likely to happen.)

Future clarification of what protection mechanisms are involved and how they are impaired in various diseases will contribute to understanding of aging (Ahuja et al. 1998; Issa et al. 2001) and various pathological conditions. (This is a single step in a huge process, but it puts us on a track to learning more than what we know now.)